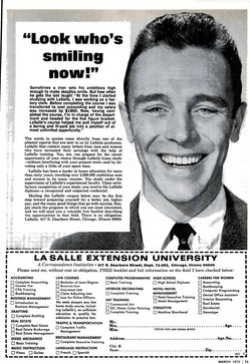

Look who's smiling now: this ad helped generate $440 million (in 2010 dollars) in just one year.

Correspondence schools took root in the United States after the University of Chicago began an innovative home study course for non-resident students. This inspired copycat businesses, and the granddaddy of them all was La Salle Extension University. In 1908, founder J.G. Chapline set up offices a few blocks from University of Chicago and began trading on their good reputation, often running ads right next to theirs in Cosmopolitan, Pearson's, National Geographic, Popular Mechanics, etc.

LaSalle offered a valuable service that helped many people. In segregated America, LaSalle offered opportunities for many African-Americans who might have had problems matriculating at their local schools. Many hard-working people with full-time jobs, including future governors, congressmembers, and senators, obtained degrees from LaSalle. LaSalle's most controversial program, their at-home bachelor's degree in law, was their greatest success, but also led to their eventual downfall in 1979. Between its meteoric rise and its decline and fall, LaSalle became the template for both University of Phoenix-type distance learning schools and diploma mills.

Like modern academia, a big part of the revenue involved selling overpriced books authored by instructors, so Chapline set up his own publishing company and recruited established authors to write textbooks. The result was remarkable. By the time the Federal Trade Commission stepped in during the 1970s to curb industry excesses like diploma mills, LaSalle had well over 100,000 active enrolled students and was clearing $75 million annually (over $440 million adjusted for inflation). Their aggressive direct response ad campaigns converted about 20% of inquiries. I pulled a few examples from their ad campaigns.

The earliest ads were small classifieds, but by 1910 they were placing display ads in Marquis Who's Who, the vanity publication still in business today. The ads showed a stately castellated building similar to those at University of Chicago. They not only located their headquarters near University of Chicago's campus, but they also placed ads next to U of C's, and even ran in U of C's alumni magazine. By 1914, they were running highly targeted ads, like the ads in International Socialist Review stating "Every SOCIALIST Should Know LAW! Become A LAWYER!"

There was always a populist bent to their ads, with their early slogan "Taking The University to the People." And they did just that, affording women and minorities a chance to get degrees. For instance, LaSalle law graduate Gertrude Rush was the first African-American woman admitted to the Iowa bar.

There was always a populist bent to their ads, with their early slogan "Taking The University to the People." And they did just that, affording women and minorities a chance to get degrees. For instance, LaSalle law graduate Gertrude Rush was the first African-American woman admitted to the Iowa bar.

Money poured in, and LaSalle began to refine their message as advertising got more sophisticated. Ads became about setting oneself apart from competitors: "Are You the Ten-pin –or the Ball?" or "The Only Way Out of a Pit– –UP!" quoting Jack London (noting he was "penniless and with only a scanty education" when he uttered this). One insidiously clever ad from 1930 was targeted at bosses, advising that a great way to blow off raise requests was to suggest the underling enroll at LaSalle and come back when he was done.

LaSalle was pulling in money hand over fist even during the Depression, which eventually brought them to the attention of the Federal Trade Commission. In 1937, FTC ordered that they no longer call themselves a University, though that order was lifted a year later. After a lull during World War II, business picked up again as GIs sought to set themselves apart from other applicants: "What's the DIFFERENCE between them? One a failure. One a success. Which One Are You?"

LaSalle was pulling in money hand over fist even during the Depression, which eventually brought them to the attention of the Federal Trade Commission. In 1937, FTC ordered that they no longer call themselves a University, though that order was lifted a year later. After a lull during World War II, business picked up again as GIs sought to set themselves apart from other applicants: "What's the DIFFERENCE between them? One a failure. One a success. Which One Are You?"

LaSalle continued to grow in the 50s, to the point that their massive revenue caught the attention of major publishing houses. Crowell-Collier acquired them in 1961, then merged with textbook publishing giant Macmillan. By then the amount of money involved had led to an increase in unaccredited schools and diploma mills. The Higher Education Act of 1965 tried to remedy that, but the diploma mills then just moved to create bogus accrediting agencies in order to meet these new requirements. In 1969, with $50 million a year at stake, LaSalle sued accrediting agency National Home Study Council for monopoly and restraint of trade. They also began advertising much more aggressively, coming up with one of their best-known and most enduring ads: "Look who's smiling now!" The ad proved to be so effective that they updated it with a groovy 70s guy.

LaSalle continued to grow in the 50s, to the point that their massive revenue caught the attention of major publishing houses. Crowell-Collier acquired them in 1961, then merged with textbook publishing giant Macmillan. By then the amount of money involved had led to an increase in unaccredited schools and diploma mills. The Higher Education Act of 1965 tried to remedy that, but the diploma mills then just moved to create bogus accrediting agencies in order to meet these new requirements. In 1969, with $50 million a year at stake, LaSalle sued accrediting agency National Home Study Council for monopoly and restraint of trade. They also began advertising much more aggressively, coming up with one of their best-known and most enduring ads: "Look who's smiling now!" The ad proved to be so effective that they updated it with a groovy 70s guy.

Alas, all the ads in the world could not help them escape the FTC, who sued them for misrepresentations about obtaining law degrees through a correspondence course. Following further litigation, LaSalle finally folded in 1980. Out of the ashes of the regulatory firestorm during the Carter Administration, a new challenger appears, rising like a… well, a phoenix. The University of Phoenix, founded in 1976, took over where LaSalle left off, eventually making the leap into the digital age. Their aggressive advertising uses the LaSalle model and has been even more successful than LaSalle: their holding company Apollo Group (NASDAQ:APOL) clears about $3 billion a year.

I created a Flickr set of LaSalle ads for those interested.

This piece is based on several articles I originally wrote for Wikipedia.