From 1942 to his retirement in 1966, Carl Barks drew Donald Duck comic books (7th greatest comic of the 20th Century according to The Comics Journal) for Walt Disney. He took what should have been a bland franchise and turned it into a classic of comics. Drawing on his own experiences (most notably a brief stint as a chicken farmer), Barks went to create a character who was remarkable… for not being remarkable. In his pursuit of a good job, his boredom with suburban life, his temper, his squabbles with neighbors and his resolve in the face of his many failures, Carl Barks’ Duck was truly your average American.

Lost in the Andes (1949) is widely regarded as Carl Barks' finest story, was his personal favorite, and the one he felt was his most technically perfect. Visually, it is an astonishing piece, taking us from cramped ship's quarters to the open sky above the mountains, through fog and bright sunlight, each panel masterfully rendered for maximum effect. As a story it is equally remarkable, personifying what critic Michael Barrier said of the auteur: "Barks was a writer first and an artist second, and his drawings have life because they are in the service of characters and ideas." This writing shines in "Lost in the Andes," taking us from a stuffy museum in Burbank, over a turbulent ocean to South America, up mountains, across plains, down valleys, and into a fog-shrouded land with strange people who speak like Southern Gentlemen from Alabama, with a heroic and curious Donald and brave and intelligent nephews who end up saving themselves from a life sentence in prison. For once, Donald is not motivated by greed or heroics, but curiosity and a taste for adventure. It is a morality play about happiness and a neat character study of the Ducks. Critics such as Thomas Andrae have examined "Lost in the Andes" and argued, quite effectively, that it possesses acidic criticisms of the capitalist system, that it deftly skewers the "myth of the explorer" and colonialism, while also managing to hold a mirror up to the closemindedness of preindustrial cultures, albeit ones that have been essentially colonialized. Like any masterpiece, "Lost in the Andes" means many things to many critics, each one finding something new with every reading.

But it is also a story about eggs.

Carl Barks was once an egg farmer, and this profession appears to have influenced more of his stories than any of his other failed efforts. Here, as in "The Magic Hourglass" (and a story not mentioned here, "Omelet," worth seeking out), eggs get things rolling. Even though these eggs don't roll.

"Lost in the Andes" begins quietly in a natural history museum, cleaning time at this hallowed institution. In the opening splash panel, we have a narrative box explaining that Donald is the fourth assistant janitor, and he's being ordered to clean by the third assistant janitor—a joke in and of itself, a stick in the eye to either the bloated bureaucracy of a major public museum, or to wage slaves and their need to be superior to someone, anyone. Donald wears the eager look of a man intent on his work. His superior seems like a total jerk. Our hero's assignment? To polish stones.

From this lowly moment in Donald's life the adventure begins. Donald is supposed to clean years of accumulated dust on "ancient Inca ruins," including what appear to be square stones. Here, Donald's clumsiness is a boon: he drops one of these stones, and is shocked to discover it breaks open on the floor, spilling its contents. The rocks, as it turns out, are eggs. By the end of page two we will see Donald and his nephews aboard an expeditionary boat to Peru, and along the way there's a sudden, breakneck pace to Barks' paper movie, the montage of discovery.

"Donald's accidental discovery startles the scientific world!" In a wonderful, page-wide panel, Barks shows eleven scientists studying and arguing over the eggs. What a collection of, well, eggheads. They are bearded in most cases (including one fellow who is nothing but a pair of eyes in the midst of a shrub of facial hair), though the one who is not stares at the others through a pair of bottle-thick specs and has nothing but wrinkles, like a shar pei. In the next panel, a pair of fat, egg-headed, wealthy "egg dealers" (with diamonds on their shirts), are literally drooling with anticipation of what these eggs can do for their industry (and the fact that one of them fondles a square egg suggests that the scientists' forthcoming journey is going to be underwritten by these unpleasant people.) Next, we see a pair of rube chicken farmers "agog" (in Barks' words) over the possibilities as well. One of the things I've always loved about Barks is his attention to background detail, and especially the jokes he puts in the form of signs and shapes. In the panel with the fat-cats fondling the square hen fruit, you'll notice there's a graph with the name "Interglobal Eggs — 'Something to Cackle About!'" on the wall, and the globe in their office is egg shaped. As the farmers yak on about the possible bounty of "square fryers with round corners," one of the roosters is looking on, sweat flying from his brow. The ships, the offices, the farms are rich with this background detail, but detail that helps us slow down to appreciate each panel of the story.

Once everyone gets on the boat, we see a reprisal of the hierarchy that existed at the museum, a system that Donald will be free from thanks, again, to eggs. The discovery of the square eggs released Donald from the walls of the museum, as he is hauled along on this expedition with only his nephews beneath him in the pecking order. In a weird but hilarious sequence, the top scientist demands an omelet from his assistant, Tombsbury. He, in turn, demands his assistant, Wormsley, make it instead (in a panel that has a strange noirish tilt to it, shot from a god's-eye-point-of-view and looking like a lost frame from Orson Welles' Lady From Shanghai). Wormsley, without any of the dignity he or his supervisor received, shouts at Donald, whose name he doesn't even know — "Hey you! The prof wants an omelet! Get busy!" Our hero, chest puffed out, calls for "Assistants Four, Five, and Six…" to make the omelet. These are, of course, Huey, Dewey and Louie, who are all blowing gum bubbles.

Once everyone gets on the boat, we see a reprisal of the hierarchy that existed at the museum, a system that Donald will be free from thanks, again, to eggs. The discovery of the square eggs released Donald from the walls of the museum, as he is hauled along on this expedition with only his nephews beneath him in the pecking order. In a weird but hilarious sequence, the top scientist demands an omelet from his assistant, Tombsbury. He, in turn, demands his assistant, Wormsley, make it instead (in a panel that has a strange noirish tilt to it, shot from a god's-eye-point-of-view and looking like a lost frame from Orson Welles' Lady From Shanghai). Wormsley, without any of the dignity he or his supervisor received, shouts at Donald, whose name he doesn't even know — "Hey you! The prof wants an omelet! Get busy!" Our hero, chest puffed out, calls for "Assistants Four, Five, and Six…" to make the omelet. These are, of course, Huey, Dewey and Louie, who are all blowing gum bubbles.

Like the pencil stub in "Maharajah Donald," the nephews' gum bubbles are a clue to a future solution. Without finding any eggs, the boys use what's available, and follow orders, making an omelet from the square eggs — you know, the eggs that are decades old.

As the plate of rancid omelet is handed off from assistant to assistant, each man, hungry I guess, takes a small bite, and by page five each and every member of this expedition — with the exception of the nephews — is sick beyond belief (with "Acute Ptomaine Ptosis of the Ptummy!"). When the ship finally lands in Peru, the same hierarchical chain rejects the idea of chasing after square eggs, having lost interest thanks to their sickness. Donald, being near the bottom, thinks to send his nephews, but decides to go himself when he sees them blowing bubbles. Apparently he believes that he's the only one mature enough to lead this expedition.

Outside of the thrill of watching this story unfold, of the madness of square eggs and the rather ridiculous way the expedition has at once unraveled and sent our hero on his way, what strikes me as significant here is Donald's motivation. Though we know that Donald is going to fumble and bumble along the way, much to our joy, he's also a much richer character now than he was in, say, "Maharajah Donald." He's someone with direction, brave, pushing through to find the source of those square eggs. Do we think to ask why? Consider: as Thomas Andrae points out in his remarkable Carl Barks and the Disney Comic Book, Donald has never received credit for the initial discovery of the eggs (not that accidentally dropping one while cleaning is worthy of tremendous accolades), but Barks has pretty much established that Donald isn't going to get anything more than his day's wages for this dangerous journey — wages which I can't imagine amounts to much.

And yet, in the treacherous mountains of Peru, Donald and the nephews push on, despite numerous failings (all of which are funny), even going so far as to climb to the "the highest plateau in the region!" and then, "[m]iles and miles and miles later," feeling more frustrated than exhausted, the clan comes across a very old fellow who speaks of an American who passed through and into the "region of the mists." This American returned with "a look of madness," cold and hungry. Armed with this news, the ducks practically race into the mists, even as the old man tries to call them back to warn them that no one but that American had ever returned.

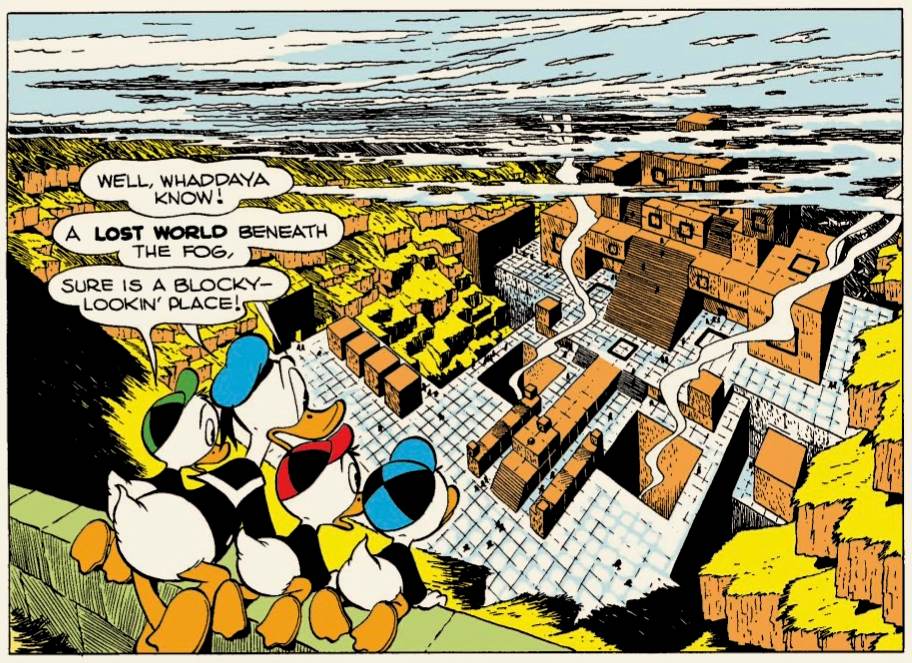

What's amazing to me is that we're not even at the heart of this story, and already so many great things have occurred. The ducks plunge into fog (in perhaps the only section of the book I don't find all that visually intriguing — Barks rendered the ducks in the fog as dark lines, to represent the difficulty of seeing them, but they all come off as stiff.) Our heroes slide down a grassy slope and into a warm valley, where the fog thins out and everyone can see suddenly. And there is perhaps Barks' best splash panel: "A lost world beneath the fog!" Donald whispers (I assume), and an amazing panorama (which Barks claimed he screwed up, perspective-wise, though it's very hard to notice). "Every bit of it is built with square blocks," Donald notes.

Once down the slope, Donald and his nephews again bravely confront a new culture, men and women with squarish heads, boxy noses, and speaking, inexplicably at first, in a southern accent. In fact, the first "native" they encounter is singing "Dixie," one of the most charged songs a person could imagine hearing from the mouth of a lost culture from South America.

Once down the slope, Donald and his nephews again bravely confront a new culture, men and women with squarish heads, boxy noses, and speaking, inexplicably at first, in a southern accent. In fact, the first "native" they encounter is singing "Dixie," one of the most charged songs a person could imagine hearing from the mouth of a lost culture from South America.

Inca-inspired, fog-shrouded paradise where the only cuisine is eggs prepared in the usual way — fried, poached, scrambled, boiled. And yet, no chickens. Ushered to the dining table of the President, the ducks fear they're going to be eaten, but really this is the Awfultonians serving our heroes dinner and showing off their "Southern Hospitality." Barks likes to throw in weird little asides, such as one of the nephews (hat free, so who knows who's saying what?) stating "I hope we have filets of spring vicuna with wild rice dressing!" What? No, kids, you're getting eggs, and here Barks' comic timing asserts itself. As Donald peppers the Prez with question after question, interspersed within this dialogue is the kids' own deflating expectations as course after course of eggs comes their way ("Second course… scrambled sggs!"). Turns out an explorer, the "Professor from Birmingham" (Alabama, natch, and spelled phonetically: "Bummin'ham"), "discovered" this ancient city. Such was his influence, apparently, that the whole culture accepted his name for the place (Plain Awful), took his language, took his accent, took his favorite music and even took his country's system of government, as they have a President, make the Ducks Secretaries of Agriculture, etc. So while the U.S. doesn't seek to colonialize, our imperialist system of setting up submissive democracies exists even in Barks' universe.

Inca-inspired, fog-shrouded paradise where the only cuisine is eggs prepared in the usual way — fried, poached, scrambled, boiled. And yet, no chickens. Ushered to the dining table of the President, the ducks fear they're going to be eaten, but really this is the Awfultonians serving our heroes dinner and showing off their "Southern Hospitality." Barks likes to throw in weird little asides, such as one of the nephews (hat free, so who knows who's saying what?) stating "I hope we have filets of spring vicuna with wild rice dressing!" What? No, kids, you're getting eggs, and here Barks' comic timing asserts itself. As Donald peppers the Prez with question after question, interspersed within this dialogue is the kids' own deflating expectations as course after course of eggs comes their way ("Second course… scrambled sggs!"). Turns out an explorer, the "Professor from Birmingham" (Alabama, natch, and spelled phonetically: "Bummin'ham"), "discovered" this ancient city. Such was his influence, apparently, that the whole culture accepted his name for the place (Plain Awful), took his language, took his accent, took his favorite music and even took his country's system of government, as they have a President, make the Ducks Secretaries of Agriculture, etc. So while the U.S. doesn't seek to colonialize, our imperialist system of setting up submissive democracies exists even in Barks' universe.

But where do these eggs come from? Themes repeat themselves in "Lost in the Andes:" the ducks discover the source of the eggs, square chickens that look like rocks. They find them when the boys blow a gum bubble and stick it to a square boulder, which turns out to be the slumbering fowls, who react angrily. When they're rewarded with their appointments to Secretaries of Agriculture, the boys reveal how they discovered the birds, and the Awfultonians freak out: round bubbles in a square culture? Blasphemy! The boys have violated the "only law" (no one steals or kills here). "It is chiseled in th' statutes that whoevah projuces a round object mus' spend the rest of his life in th' stone quarries!" the President proclaims. Because of their heroics, they get a second chance: the boys must blow square bubbles.

Round vs. square, chicken and egg. Needless to say, the boys succeed, but even after this success, how do they escape Plain Awful and get back home? Well, it was the museum that set them on this journey, and it is a museum that sends them on their way back — the museum of Plain Awful has on display a compass, which the ducks trade for square dance lessons (which is, of course, a dance performed in a variety of circles.)

Emerging from the fog, our heroes pause, with a pair of chickens in a case on their backs, and reflect on the happiness of the Awfultonians, people who, Donald notes, have "never seen the sun," but "were the happiest people we have ever known."

So why not stay? Well, if we go by the rules of the Campbellian hero's journey, our man must return to his own culture, return with the spoils of his quest. For once, Donald expects to get some credit — in fact, we see him radioing the museum from the ship, sitting at the table with the scientists as they study his chickens, proud of his accomplishment that will change the poultry industry forever… until one hilarious mistake upends this entire expedition.

Again: the question that plagues me is "why?" Why is this lowly factotum pushing himself and his nephews — up mountains, into a "lost world," and back again — on this maniacal quest for square eggs? Yes, "Lost in the Andes" can be seen, as Andrae so eloquently states, as a critique of capitalism and Donald's vast failures, his inability to make money or find success. But this is the thrust behind the Barks' Donald Duck comics as a whole I think — that Donald is someone who just wants more out of his life, which I find exhilarating and inspirational. As a child, we gape and marvel at the opportunities afforded to the nephews, and something so childish — gum bubbles — both push the kids into peril and get them out of the same. For adults caught in meaningless jobs, Donald represents that heroic dream — that some happy accident will come along when we least expect it, and send us on a journey. Donald has no illusions that he's not going to make any money, or at least doesn't speak of any kind of remuneration. Instead, he presses forward, for the thrill of adventure.

This is what Donald does for us, but perhaps most importantly, perhaps this is what he did for Carl Barks himself. The man was paid all of $925 for his work in that comic book, $800 of which represented his payment for "Lost in the Andes." Walt Disney's Comics and Stories usually sold close to three million copies, but let's be conservative and say that issue sold only a cool million — that means Barks commanded a sweet nine ten-thousandths of a cent per issue (had Disney given him just a half cent per issue, Barks would have made five grand by the same estimation, which would have no doubt made him insanely happy.) By this time (1949), Barks was barely making it as a writer/ illustrator for Western Comics, was sinking in the morass of a second, disastrous marriage (to a drunk), with a pair of daughters from the first bad marriage and few prospects outside of this work. Armed with that stack of National Geographics and an Encyclopedia Brittanica [which he used as reference material for his drawings and scripts – ed] , trying desperately to forget the living hell of his domestic life, he created in his hero an everyman who could do what he could not — escape. Certainly, he critiqued capitalist hierarchy, and used this Inca-like culture to his benefit. He shared with us his need for escape, revealing that the journey is its own reward.