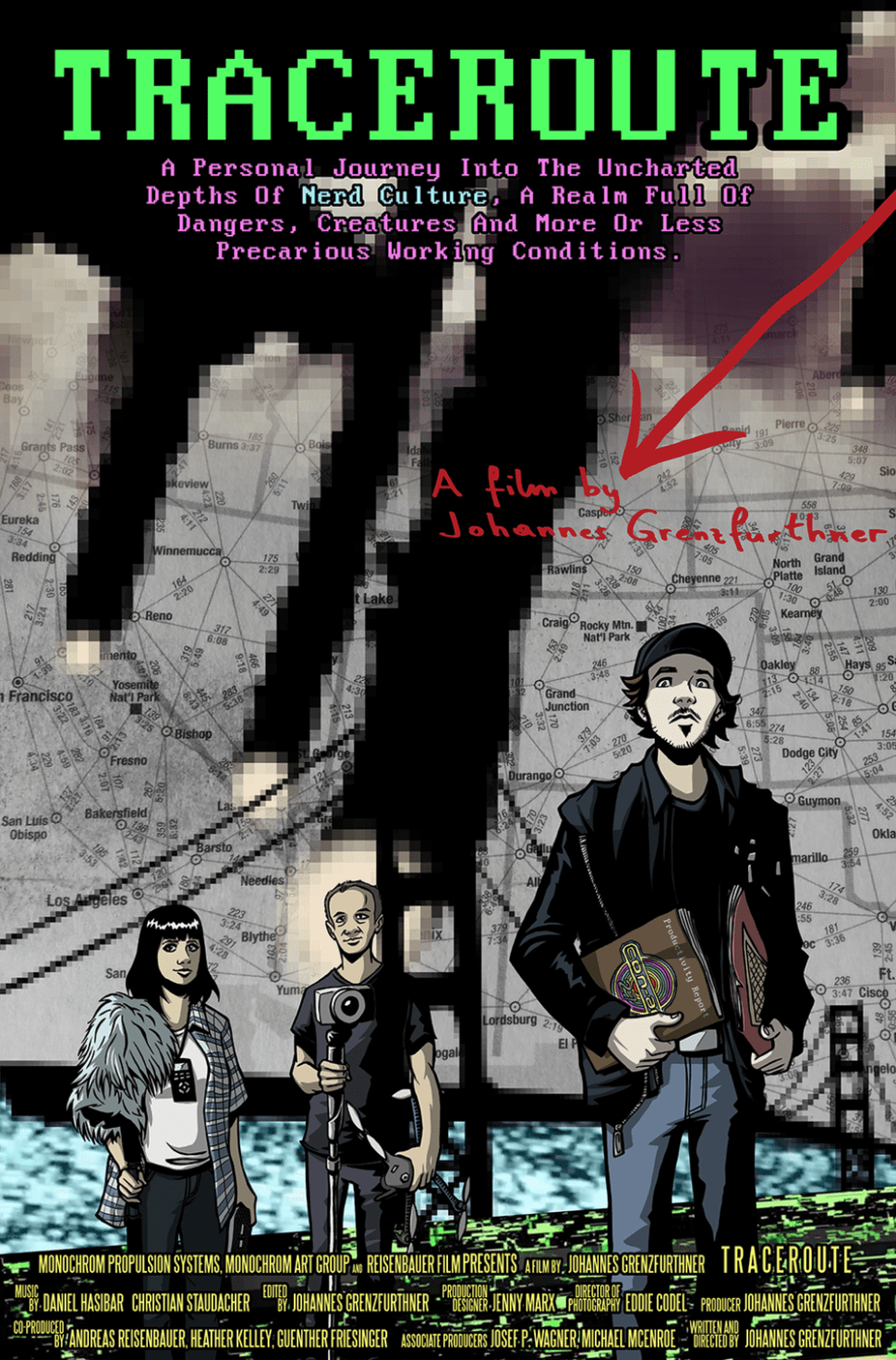

In the documentary film Traceroute, Johannes Grenzfurthner stuffs 40 years of his life as a nerd into a fast-paced road movie. The result is a brilliantly careening biography of a highly enigmatic species. Thomas Kaestle had the opportunity to see the upcoming film. And then he talked to the filmmaker about passion, references and the whole rest.

“A brilliant lunatic of surpassing and delightful weirdness.” Anybody who is characterized with such enthusiasm by Cory Doctorow on Boing Boing doesn’t really need the small print any longer. And yet it is still worth going to the trouble. Precisely for the reason that Johannes Grenzfurthner has been living the heterogeneous and yet wondrously contingent life of a model nerd since his earliest childhood. Born in the Austrian provinces, he spent his first 17 years as an author, director and actor of secret agent and science fiction films, as a constructor of time machines, and as a consumer and producer of cyber and punk.

Then he founded monochrom as an alternative magazine for art, technology and subversion, on the quest for the “most effective weapon of mass distribution”. That was way back in 1993. He rapidly conquered all the media that could be conceived of at the time, and he became a pioneer of urban hacking and coined the concept context hacking. He teaches at the art universities in Graz and Linz, directs productions at the Vienna Volkstheater and makes feature and documentary films. He heads the festival Arse Elektronika (conference for sex and technology) and is co-organizer of Roboexotica (festival for cocktail robotics). He splits his time between Vienna, Colorado and anywhere else he happens to be.

The basic idea behind Traceroute is as simple as it is effective: Johannes Grenzfurthner travels through the USA from the West to the East Coast – on the trail of people and things that made a mark on his life as a nerd. Aliens, dinos, meteorites and rockets. Film locales, graves and no-go areas. Authors, collectors, tinkerers, outsiders and nuts. Nerds of every sort and color. Traceroute is radical individual empiricism, a narrative biographical puzzle and an experimental projection matrix. Despite continual stimulus satiation, it is wonderful fun: the film tickles the synapses with a perfectly mixed cocktail of collectively shared context and a quirkiness that takes some getting used to. Whoever might be proud of having been able to interpret all of the film’s cinematic references has perhaps just missed the next pop-culture innuendo in the soundtrack. Traceroute is at once playful, challenging, encyclopedic: and it is a sentimental journey to boot. As a documentary it is constructed with unusual cleverness. And as a narrative it is universally compatible – at least it will capture the hearts of avowed nerds everywhere, and touch the rest of us who need a little explanation.

You place a quote by Margaret Atwood at the beginning of your film: “In the end we all become stories.” And you do actually make yourself, with all of your stories, into a narrative. Albeit one that is associative, incomplete. Is this the way biographical memory works? Is it always a narrative construction? Is there any claim of “truth”? Or would people who know you recount everything very differently? And: is biographical memory worth more or less as a good story?

The human is a narrative being. We construct emotional machines, so-called “stories”, to communicate, to share the world in which we live and make it collectively experienceable. And we are pretty good at doing that. Since the primordial soup at some point mendelized into primate brains, we have either been fleeing from big cats or telling others about our escapes from the clutches of big cats. Sitting around the campfire, interpreting and breaking down the world, charging it with aura. Initially this was all very mythopoeic, and slowly it became more differentiated. But even in the post-Enlightenment age, world interpretations are not necessarily particularly rational. Good stories sell well, and the best stories are the ones that hit you in the gut, regardless of whether they would hold up to a Wikipedia check or not.

As individuals we believe that we are logical, autarkic, self-contained units. We experience ourselves as something homeostatic and constant, and this neurophysiological deceit is a truly wonderful thing. We are the managers, historiographers and censors of our own existence. We create our self-perception from a host of fragmented thought splinters and shreds of memory… and we do it on the fly. We are the architects of the new subject. And of course it is particularly exciting to hear, read and see the narratives that others disseminate about us. That is, after all, what remains behind when we are gone. Do I want to be perceived that way? And when is it time to call my lawyer, if I start getting the feeling that the stories my fellow humans are telling about me no longer have anything to do with my own?

And what about the self-perception of entire groups? How do attributions and identification templates like “FC Bayern fan” or “Thrash Skater” or “Lego Mindstorms aficionado” develop. What is the true nerd? Yeah, well… actually I would be a little careful about any conceptions of truth. You can track an awful lot of dirt into your living room that way.

When you talk about the “self-perception of whole groups” you are, on the one hand, avowing the nerd’s gaze inward upon the nerds. On the other hand, you also imply a transferability or representativity. Are you offering the story of how you became a nerd to others as a model for identification? Is Traceroute primarily a film for nerds? Do you have any idea how people who have not since their earliest childhood devoted themselves to Star Trek, WarGames, GURPS, Lovecraft, aliens or dinos will experience your story? Deftly, you leave attempts at formulating definitions up to others. How heterogeneous do you consider the nerd “group” to be?

Heterogeneity is an almost identitary aspect of being a nerd. There are so many groups and splinter groups, interest concentrations and animosities. That is why I started my film autobiographically. I think that there are very different ways of becoming a nerd, and that personal moments of bliss or trauma can be very far apart. Nonetheless, I think that certain patterns do exist, particularly when I look at the stories of the nerds of my generation. I try to get to the bottom of these patterns in Traceroute, but in doing so I attempt to be as little like Werner Herzog as possible. Through my self-narration I introduce myself as a friendly alpha nerd, who takes off on a road trip through his own past and meets up with others, reflecting as one of this crowd on the ones in this crowd, but also reflecting as a fan on fans.

It is a film on biographies and obsessions and spaces of possibility – in other words something between loving embrace and merciless vivisection. Maintaining a critical meta-outlook was just as important to me as abandoning myself to unfathomable stammerings of adoration. And that all works for one simple reason: because I take a step forward, introducing myself and confessing my guilt like in Alcoholics Anonymous, only to then take off and visit the best whiskey distilleries. In my case these destinations are not whiskey makers, but people and places and symbols of a very special pop culture.

On the basis of the first test screenings, I can confidently assert that both the savvy and the clueless will have a great time watching this film. Irregardless of whether you know D&D or not, the obsession, the shame, the interest, the joy in eccentricity are well known. I have this nice little anecdote: A well-built guy at one of the test screenings, a snowboarder and kayaker and American football fan, came up to me after we had watched the film together and said kind of remorsefully: “I would never have thought it, but I think that I am actually a nerd too. I like coral. I collect it, and I know all of the Latin names. I even have a piece in my wallet. Here, have a look.”

Isn’t that going a little too far: a coral collector as a self-declared nerd? Then the old coot who collects Nazi militaria and Landser mags would also be a nerd. And really anybody who is passionate about this or that hobby. Is it so simple? Or are not certain genres, affinities and key stimuli indispensable.

I think that the most important thing about the anecdote is the self-accusation, the identification, the statement that “I too am a nerd.” In my film I don’t devote much attention to etymology, or to the myriad debates and distinctions (geek? Fan?). Instead, I try to present positions. Initially nerd referred to nothing more than a social stereotype, but it is precisely there that I find the semantic transformation striking. Back in the 1980s I took a licking because I was a nerd. Today the nerds rule the world. The nerd is the golden boy (and unfortunately I also mean this literally with regard to gender) of cognitive capitalism. He is a rebellious outsider, but also a tacit supporter. The nerd and his obsessions can be cultivated at a profit, as a productive Google employee, but also as a devoted Spiderman collector. The universe is a leading retailer, and the nerd likes stocking the shelves.

One can, in fact, make out two lines of interpretation in the film: the first is the capitalist one that you are mentioning. Nerds as a “driving force… embedded in the guts of neoliberalism.” The second is more revolution oriented. Repeatedly, you draw attention to points of intersection with leftist thinking. You say that nerds are “creators” and not “consumers”, and that “there is no creativity in the absence of rebellion.” A contradiction? Or more just a historical development?

No, there is no contradiction. I think that the figure of the nerd provides a beautiful template for analyzing the transformation of the disciplinary society into the control society. The nerd, in his cliche form, first stepped out upon the world stage in the mid-1970s, when we were beginning to hear the first rumblings of what would become the Cambrian explosion of the information society. The nerd must serve as comic relief for the future-anxieties of Western society. And the transformation I’m talking about is already in full swing: the police gaze of 19th- and 20th-century disciplinary society made visible the individual, which is illuminated by power. In our burgeoning technological control society, the individual is x-rayed and algorithmized. Even worse: the individuals x-ray themselves, willingly putting themselves on display.

Even the most intractable anarcho-hacker has a problem when control becomes more diffuse and subtle, less tangible. If Anonymous doesn’t realize that their media role – their role as whistle-blower, exploiter and avenger – is only a calculated function in the coercion and streamlining of the information society, then we all have a problem. Control has no rigid form. Soylent Google is made of people. And thus we have to go back to the drawing board when we start thinking about resistance.

One could, of course, ask: Can nerds even function at all in larger groups, contexts or structures? Does the heterogeneity mentioned earlier allow for this at all? When you talk about subcultures or parallel cultures in the film, about an “independent life” or “living against the grain”, then I begin to wonder if it is not constitutive for one’s self-perception and social perception as a nerd to have lived, or at least toyed with, the outsider cliche, to have felt misunderstood. One of your protagonists even names isolation as a condition for defining the nerd. At the very beginning of the film, you ironically describe Austria as a “culturally challenged country”. I myself grew up in the Swabian Alps. Often I have asked myself if growing up in deficient surroundings is not actually conducive to a certain sort of against-the-grain creative thinking. If you had spent your childhood in the “bright center of the universe”, from which you felt so distant as a child, would you have grown up to become that of which you are so proud today? Doesn’t becoming a nerd, in the end, have something to do with the necessity of having to improvise?

Absolutely! I agree with that 100 percent. If I had not grown up in Stockerau, in the boonies of Lower Austria, than I would not be what I am now. The germ cell of burgeoning nerdism is difference. The yearning to be understood, to find opportunities to share experiences, to not be left alone with one’s bizarre interest. At the same time one derives an almost perverse pleasure from wallowing in this deficit. Nerds love deficiency: that of the other, but also their own. Nerds are eager explorers, who enjoy measuring themselves against one another and also compete aggressively. And yet the nerd’s existence also comprises an element of the occult, of mystery. The way in which this power is expressed or focused is very important. There are such wonderful manifestations, like the DIY creature effects scene. But there are also aberrations, like #gamergate. Ethics are – although I try to avoid pointing any accusatory fingers – a fundamental issue in Traceroute.

You illustrate your ethical ruminations with things like the folkloristic shrine for Wernher von Braun at the US Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville. And with a trip to the grave of H. P. Lovecraft in Providence. In the first case, you just show this tunnel vision in regard to any sort of critical context: the celebration of a genius in the USA without even any passing mention of his inhuman role in National Socialism. But in the second case, you explore your own querying of an idol. You say that exploring the issue of Lovecraft’s racism represented a key step in your development. Where, precisely, do you think the ethical boundaries of nerdism are? And what demands do you make of other nerds?

To answer in the words of a nerd classic: “Be excellent to each other!” (from Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure). The problem is that the look outside the bubble, which the nerd has inflated around himself, is feared and avoided. There is a sort of well-manicured and privileged ignorance. And also a well-manicured know-it-all attitude. Often that doesn’t leave any room for ethics. Or ethics gets turned around, as it has on a number of occasions in the Skeptical Movement around Richard Dawkins. There the most awful sexism, which appears perennially in the community, is swept under the table and justified with conspiracy theory bullshit, just to protect the “movement” and the “progress of humanity”. Really? Or, as you are very right in mentioning, there is the political short-sightedness and negligent ahistoricity of the space fans.

Traceroute is 120 minutes long, and yet it is much too short to explore all of these interesting discourse niches. Nevertheless, I am happy that I can address a number of the most important issues in my road trip essay. Perhaps this will trigger further debate.

Often I have the feeling that nerds are primarily oriented toward contexts. The thought comes up in the film that the nerd is searching for “something out there you can connect with,” in other words for contexts in which you can live out your passion. One of the protagonists finds this sort of basis in “the soothing fact that there is always an answer in science.” You yourself speak of art as a point of reference, that you transformed yourself from “some nerd” into “some artist”. At the point in the film where you present an inconspicuous tunnel mouth as the location at which three famous film scenes were shot, I was struck by the way that nerd knowledge is often powered by contextual knowledge, by the construction of relationships. Traceroute runs at a crazy tempo, with layered images and fades. The viewer can hardly decipher all the codes, allusions and levels of readability. Is this sort of complex overflow a nerd format? Or is it just your artistic approach? Or both?

Both. Context is king in the nerd world. Definitively. And your analysis is correct: linking and celebrating knowledge is a key aspect of the nerd’s existence. The quick-cut style and referential abundance of Traceroute are both a homage to and an expression of nerdism. With regard to my existence as an artist, as a filmmaker: since time immemorial, context has been a central aspect of the artwork, albeit one that was long inconspicuous and at times invisible. Relatively recently, the context-oriented methods of modernism had to invest great efforts in returning it to the field of vision. All this effort was necessary because of the bourgeois art gaze’s tendency to fade out the social and historical embeddedness of an artifact or an aesthetic approach. Instead of context this gaze puts the creating subject at the focus of attention: it is not the contextual framework and the conditions of production that are decisive for the creation of art, but the inner state and disposition of the artist, in other words that particularly receptive and highly individual subjectivity which allegedly differentiates him from people like you and me.

Since the advent of modernism, artists have been seeking to loosen the entanglement of work and subject, because they saw themselves pushed into a role that they did not necessarily want to occupy: one which offered freedom and independence on the upside, but in combination with isolation and powerlessness on the downside. While the workers of the Fordist factory developed collectivist strategies to pursue their goals, the particularities of the artist’s existence – cast as productive eccentricity and manic-depressive individualism – made it more difficult for artists to organize to achieve their demands and improve their precarious living and working conditions. It was only with great difficulty that this group, condemned to autonomy, could free itself from the prison of its freedom.

Here Traceroute clearly dares to go on a tightrope walk. It plays a game with the tormented nerd and the suffering artist subject. And with what happens when you send them off on vacation together. All in all, one might even say that this is a little Context Hack …

While you are speaking of going on vacation… Traceroute lives from its highly European view of the USA and its cultures. For a nerd with an Austrian, or German, CV this is highly understandable. A considerable part of his possible references, buzzwords, genres, tropes and milestones are rooted on the other side of the Atlantic. You use Romero’s zombies as a device for thematizing the critique of capitalism. And for you, fantasy is not Tolkien, but Steve Jackson Games and GURPS. Actually, you do once toast Terry Pratchett. But that was it, with regard to good old Europe. Would such a film have even been possible in a different culture? Would nerd culture even exist without the USA? And to what degree is this all historically determined, tied firmly to motifs of the 1970s and -80s, like Wargames, “TV snow”, Poltergeist and the Vietnam trauma in Jacob’s Ladder? Is there a reference bible for next-generation nerds, or will they develop their own interests, things about which we dinosaurs won’t have a clue?

Oh, Tolkien, that miserable Catholic. He even hated refrigerators. A technophobic academic who probable would have fucked Ireland, if Ireland were fuckable. If that is fantasy, then it is better to learn about fantasy through GURPS rulebooks or Henson’ Dark Crystal. Of course my pop socialization was mainly American. To this very day, science fiction has the aura of trash literature in the German-speaking world, and an affinity for technology was never really a virtue there. Efficiency and quality yes, but not innovation.

With regard to the American influence, there were three decisive factors: first, the great PR successes of science during the late 1960s and the 1970s were all “made in the USA”, and thus my gaze was always cast westward. Second, I come from a bourgeois background, which in the 1980s was pro-American. Third, the relevant cultural products all came from there. Period.

I grew up at the tail end of the great future euphoria, during the shift to “no future”. But in the field of cultivated critical dystopia the USA was pioneering as well. Films like Robocop were simply unbelievably important artifacts for me, because here I found an exciting opportunity to absorb social critique. At the age of 13 I was an enthusiastic cyberpunk reader – and I was already very interested in abstruse underground stuff, primarily because I had a modem in the early days and became a part of the BBS scene. Then at 16 or 17 I went on from cyberpunk to punk itself. And so you could say that my personal history in the counterculture began with inner-American dissidence, with Re/Search, Mondo 2000 and Survival Research Labs.

I was (and am) easy to enthuse, and I have always been interested in new ideas. Still, I am also a classic, “yeah, but” sayer. Take robotics, for example, which has always been a hobbyhorse for me. For decades, AI researchers have been going spastic in a way that is not very pretty to watch. Modernity was looking toward the moon as the next step in the big future of mining and looting, and at first it all seemed possible. The first artificial brain was prognosticated for the turn of the millennium, but de facto in the year 2016 I don’t even trust my toaster. In that respect I really am a dinosaur, because I have retained a bit of dignity and a bit of respect. I was always on the progressive side, but I didn’t go along with everything. I didn’t take the jump into the hell of neoliberal Silicon Valley adulation. There is no need for a reference bible; it is enough to cite Foucault here: “It is not important WHAT you want to know, but WHY you want to know it.”

How does the transatlantic perspective look from the other side? Are U.S. nerds interested in faraway Europe. Is Traceroute, for Americans, only an exotic tale of a “crazy Austrian”? Or do you tell a story for an international audience, which is going to see your film in more or less the same way everywhere?

In the last decades, nerd culture has become quite a bit more international and polyvalent, and of course this is most of all thanks to the internet. It has become much easier to obtain information, and social deficits have become easier to manage online. My roots are in Austria, but really the story that I tell is universal. My trip through 40 years of personal nerd history, and through the collective story, would work just as well the other way around. Jerry-Lee Zakrzewski of Des Moines, Iowa travels through France on the trail of Moebius, Alphaville, Airbus and René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur… Why not?

Traceroute draws a number of links between nerd culture and sex or porno. Is that just one of your personal focuses? Or does the sex positivity you address have a collective basis among nerds? Is it abetted through a certain openness? Courage to be different? The ability to get involved in new things passionately? Or is sex, as one of the protagonists explains, a “driving force for technology”?

We live in a patriarchal system, and that is obviously not any different among the nerds. At times it is even really awful. Difficult topic… But alongside raising justified criticism, I also wanted to take another look. The classic image of the nerd, who has no girlfriend, can of course be played out ad nauseam, but I wanted to widen the panorama.

From the ancient cave drawings of a vulva to the newest live porn online game, technology and sexuality have always been closely intertwined. No one can predict what the future will bring, but the course of history up to the present indicates that sex will probably continue to play an important role in technological development in the future – and that technologies and their implementation will shape human sexuality. The question is not if, but how this interaction will continue to transform humanity. Teledildonics and sex machines, bio hacking and screw-it-yourself, bodies with expanded sexual possibilities, erotic-genetic utopias and the multiplicity of perspectives on gender and sex have long been a focal point of literature, science fiction and pornography. Thus – and here I don’t want to give too much away – interviews with activists like Kit Stubbs are also essential parts of the documentary.

In the USA your slightly more well-established colleague Michael Moore recently spoke in an interview about a fictive Austrian filmmaker, who reports on things like Silicon Valley and iPhones, but not about mass shootings. One cannot, after all, address every issue when one visits a foreign country. Thus his new film about Europe also picks out and focuses on things that work better in the USA. Is the example he mentions a coincidence? Or do you feel that he means you? On Facebook, at least, you comment that you feel a challenge has been spoken. Why? Should one show the very ugly sides of the USA after all?

Yeah, Eddie Codel, our director of photography on Traceroute, sent me the Moore interview. And of course that is a big coincidence – but an exciting one. I have accepted the challenge, and already long since fulfilled it, and I also let Moore know about that in a tweet. The film is not about showing the ugliness of the USA, but about presenting a social pastiche. I can very well adulate a commercial product AND reflect on inner-American problems. That is what makes it exciting. N’est-ce pas?

What sort of audience are you seeking to address with Traceroute? And where and when can these people see the film for the first time?

Really, I am happy about any- and everyone who comes out to see the film, regardless of which direction they come from. They should have a good time – overeat on popcorn, and hopefully not be bored. We have submitted the film to a number of festivals, many accepted it, and that’s most likely only the beginning. World premiere is on April 28 at the NYC Independent Film Festival.

For me, as a digital native, the film festival circus is a bit suspicious, I have to add. It has a whiff of market manipulation to create artificial scarcity, but there I just play along. It’s fun, and it feels like taking on a new role. Maybe I should already start thinking up a nice Nazi gaffe for a press conference, like Lars von Trier… But very pragmatically: I think that Traceroute will show up soon at an indie cinema near you. (Current festival and cinema dates are available here.) And if not, it is only a question of time how long it will take for it to show up on Pirate Bay. Cheers!

Link to Traceroute movie page: http://www.monochrom.at/traceroute/

Translation: Christopher Barber

First published on Zebrabutter